European Parliament toughens goals for UK to reach a trade agreement

Following the UK’s departure from the EU with effect from 1 February 2020, the European Parliament has now set out a tough position for the negotiations on the future relationship between the UK and EU.

MEPs have put the price of Prime Minister Johnson’s ‘ambitious free-trade deal’ such that the UK must follow EU policies in a host of areas. These range from chemicals regulation to climate change, food labelling and subsidies for companies. Further, there will need to be ‘dynamic alignment’ – with the UK adopting European rules as they are introduced.

The wide-ranging resolution also called for measures to ensure that Brexit does not cause gender discrimination, for a crackdown on all British overseas territories that may act as ‘tax havens’, and for a joint UK-EU position at the upcoming UN climate conference in Glasgow in November.

The European Parliament is establishing the mandate for the EU’s chief negotiator, Michel Barnier. They go further than Barnier’s own draft, published in early February, where there was no mention of alignment – and definitely not the automatic kind.

A first revision came from EU from national governments. It added a reference to the need for a ‘level playing field’ – commitments by the UK to fair economic competition to prevent European businesses being undercut by their British rivals. The goal of ‘building on’ existing access to British waters for European fishing boats was upgraded to ‘upholding’ it; and the UK’s participation in the Galileo satellite positioning system was downgraded from ‘should’ to ‘could.’

MEPs have now gone a step further. The European Parliament can be ‘bad cop’ – allowing Barnier to say he can’t agree certain things ‘because the Parliament won’t accept them.’

Whilst MEPs were not willing to oppose the divorce deal, they will be tougher on any trade agreement that touches on Europe’s values and social model.

European integration started in the 1950s as a way for Germany to atone for its own nationalist and belligerent past. Its citizens were eager to subsume part of their identity in a ‘post-nationalist, rules-based, non-militarist and largely mercantile entity’ – in return for being accepted again by their neighbours. Occupied at the time by three of the Allied Powers, they had surrendered national sovereignty – so did not worry about ceding more of it to Brussels.

Meanwhile, post-Brexit, the agreed ‘financial settlement’ – often labelled the ‘exit bill’ or ‘divorce bill’ – is has come into operation. The settlement is part of the Withdrawal Agreement, which is the legally binding treaty setting out the negotiated terms of the UK’s departure from the EU.

It sets out how the UK and EU are settling their outstanding financial commitments to each other – which financial commitments will be covered, the methodology for calculating the UK’s share and the payment schedule.

There is no definitive cost to the settlement. The final cost to the UK will depend on future events such as future exchange rates and EU budgets. Present estimates suggest a net cost to the UK of around €33 billion (£30 billion).

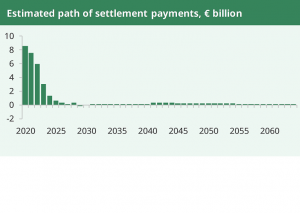

Much of this cost will come in the early years of the settlement, but the Office for Budget Responsibility – the UK’s public finances watchdog – has forecast that relatively small payments will continue until the mid-2060s.

The UK and EU have formally agreed some principles for the settlement:

- no EU Member State should pay more or receive less because of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU;

- the UK should pay its share of the commitments taken during its membership; and

- the UK should neither pay more nor earlier than if it had remained a Member State. This means that the UK will make payments based on the outturns of EU budget.

The settlement can be split broadly into three components:

- During the transition period, until the end of 2020, the UK will pay into the EU budget almost as if it were a Member State. The UK will also receive funding from EU programmes– such as structural funding – as if it were a Member State.

- EU annual budgets commit to some future spending without making payments to recipients at the time. The commitments will become payments in the future. The UK will contribute towards the EU’s outstanding commitments as at 31 December 2020. Recipients in the UK will also receive funding for outstanding commitments made to them.

- The UK will share the financing of some EU liabilities as at the end of 2020, and any materialising contingent liabilities, and will receive back a share of some assets. The pensions of EU staff are likely to be the most significant liabilities for the UK, while the most significant item being returned to the UK is the capital it paid into the European Investment Bank (EIB).

Beyond these three components the UK has, for instance, agreed to continue to contribute to the EU’s main overseas aid programme – the European Development Fund – until the current programme ends. This programme is funded directly by Member States, rather than through the EU budget. Any UK contribution made via the EU will count towards its commitment to spend 0.7% of national income on overseas aid.

The UK net payments to the EU are estimated by the OBR as totalling £30 billion between 2020 and 2064:

- 2020: £8 billion

- Between 2021 and 2028: a total of £20 billion

- Between 2029 and 2064: a total of £2 billion