Coronavirus adds further uncertainty in the event of a no-deal Brexit on 31 December 2020

The UK ended its membership of the EU on 31 January 2020 – after 40 years of increasing integration. It has been recognised by all sides since the result of the ‘leave’ referendum was announced in June 2016, that a ‘no-deal’ Brexit was anything but a ‘clean’ break. Thousands of processes, laws, regulations, shared projects and freedoms would each have to be carefully examined by each side – and the future arrangements negotiated, legislated and practicalities put in place.

Experts had suggested that the negotiations would need several years – a figure of three was mooted – to complete Brexit planning in an orderly fashion. Meanwhile, the UK and EU agreed that things would continue pretty well as they were on 31 January to allow for an orderly severance – known as the ‘transition’ period.

One key difference of opinion is that, despite being offered an extension to the transition period to 31 December 2022 should it prove necessary, the UK Conservative Government legislated for a latest end date to transition of 31 December 2020 – in line with their winning election manifesto.

The scene was set – and talks between UK and EU opened in Brussels on 3 March…but came to an abrupt halt just a few days later due to the coronavirus outbreak. The previously agreed – and already tight – timetable for the talks cannot now be met.

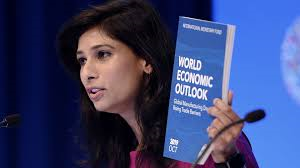

In the light of the pandemic, external observers, including the International Monetary Fund, have suggested the UK and the EU should not “add to uncertainty” from coronavirus by refusing to extend the period to negotiate a post-Brexit trade deal.

IMF Managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, was asked in a BBC interview what she thought about the prospect of a ‘no-trade’ Brexit in 8 months time. She felt that because of the “unprecedented uncertainty” arising from the pandemic, it would be “wise not to add more on top of it…I really hope that all policymakers everywhere would be thinking about reducing uncertainty. It is tough as it is, let’s not make it any tougher,” she said.

The IMF chief had previously already backed the parties reaching a deal – warning that a no-deal Brexit would hit the UK economy by up to 5%.

Without a deal, the UK and EU will move overnight to trading on ‘World Trade Organisation’ terms from 1 January 2021 – including significant new taxes and checks on trade.

Background Detail

A UK-EU Withdrawal Agreement (WA) was concluded in October 2019, accompanied by a non-binding Political Declaration (PD).

The PD set out a framework for the future relationship. Together the WA and PD provide an outline scope and timetable for the future relationship negotiations.

The WA provides for the ‘transition’ period. During the transition, EU law (with a few exceptions) continues to apply to the UK. The transition period ends on 31 December 2020 – but could be extended “for up to one or two years” if both the UK and EU agree to do so by 1 July 2020.

The PD sets out the shared intent of the UK and EU to get future relationship agreements in place by 31 December 2020. The PD includes provision for a high level UK-EU meeting to take place in June 2020 to ‘assess progress’. It commits the UK and EU to using ‘best endeavours’ by 1 July 2020 to have: concluded and ratified a fisheries agreement; and conducted equivalence assessments. Decisions on reciprocal data exchange and adequacy of security are to be complete by the end of 2020.

Before the coronavirus hiatus, the proposed timeline envisaged negotiations being concluded before the 15-16 October 2020 summit of 27 EU leaders European Council meeting.

At the time that negotiations were suspended the joint UK and EU statement described the talks as “constructive”. They said that there was agreement in some areas – but there were differences in areas including: governance, “level playing field”, fisheries, and judicial and police co-operation in criminal matters.

Despite the suspension of talks, the UK Government has repeatedly stated that it will not ask for or agree to an extension of the transition period – referring to the Conservative manifesto commitment. Indeed, the Government went so far as to legislate to prohibit itself from agreeing an extension with the EU.

Labour Party leader, Keir Starmer, has said keeping to the deadline of ending the transition on 31 December seems “unlikely”. In addition to the IMF comment, above, there have been calls by many trade and commercial organisations along with other opposition parties and MEPs to extend the deadline.

On 18 March the Prime Minister said that he had no intention of changing the legislation that prevents the Government from agreeing an extension.

In Brussels the EU trade commissioner, Phil Hogan, has said that in every EU member state, civil servants were busy dealing with the Covid-19 situation. He explained there were not enough people “who are able to apply themselves to these intensive [Brexit] negotiations that are required to be concluded in such a short space of time”. He believes that a comprehensive trade deal could not be concluded in time for a 31 December deadline.

There is already one very significant impact of the UK no longer being an EU member state. It is no longer part in the EU’s decision-making and legislative processes. Nevertheless, under the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement, all new EU laws that come into force during the transition period will apply to the UK.

Prior to Brexit, the Government said most EU law due to come into force during the transition period would have been agreed while the UK was still an EU member state, with full representation and voting rights. However, the coronavirus pandemic means the EU is having to make certain policy decisions at speed and bring new rules into force more quickly than is often the case.

The Government was also planning to use the transition period to begin negotiating new trade deals with countries outside the EU to come into force after the transition period ends. The priority was to launch negotiations with the US, Australia, New Zealand and Japan. On 24 March, however, the Government said that whilst both sides remained fully committed to negotiating a free trade deal, the ‘unprecedented coronavirus situation’ means all sides are “looking at options to conduct the negotiations in a way that reflects the current situation and respects public health”. More pressure and uncertainty for business, trade and finance in a no-deal scenario on 31 December 2020.

Our team has modelled the requirements for managing a no-deal scenario – and businesses across the EU and UK now risk adding these onerous additional impediments to free trade to a global economy that has been undermined and weakened by the impacts of Covid-19.

References: